There have been millions of words written and spoken about ‘informal’ and social learning over the past few years.

In fact, if a Martian had just arrived on Earth and strayed into a meeting of Learning and Development professionals or into a learning conference, or even picked up a professional journal, he would logically assume that these were the only ways humans learned.

The Martian’s assumption would be roughly correct. Humans learn principally through the process of carrying out actions, making mistakes, getting help from others, having discussions about which approach to take, stepping back and reflecting on why ‘it isn’t working’ and using a myriad of other strategies in the heat of the workflow or activity.

The shift in focus to workplace and social learning by HR and Learning professionals over the past few years is an significant one. And it’s not just a passing phase or fad. It is reflecting a fundamental change that is happening all around us – the move from a ‘push’ world to a ‘pull’ world, and the move from structure and known processes to a world that is much more fluid and where speed to performance and quality of results are paramount.

Social and Workplace Learning

The increased focus on social and workplace learning is causing considerable disruption in the L&D world both to the traditional roles for those who are designers and delivers of courses and programmes and also to the whole ecosystem of training and learning suppliers that inhabit the L&D world providing programmes, courses and content and the supporting infrastructure to deliver (mainly) learning and development events.

The increased focus on social and workplace learning is causing considerable disruption in the L&D world both to the traditional roles for those who are designers and delivers of courses and programmes and also to the whole ecosystem of training and learning suppliers that inhabit the L&D world providing programmes, courses and content and the supporting infrastructure to deliver (mainly) learning and development events.

In a way, what we’re witnessing is a significant shift in thinking about the best ways people can keep abreast their jobs and improve performance in a world where change is not only becoming the norm, but is accelerating on an almost daily basis. Other factors such as the changes brought about with new generations entering the workforce and technology changes creating participatory learning opportunities (as pointed out recently by Claire Schooley of Forrester Research) play their part.

A number of approaches are emerging to meet this changing thinking.

Our awareness that more learning occurs outside courses and curricula than inside has added fuel to the fire of social learning – which was lit by the plethora of emerging social media tools and technologies speeded on their way by events typified in the O’Reilly Media conference in 2004.

Also, there has been a re-awakening of the understanding that context is vital for learning and, aligned with this, that performance in a formal training environment is not necessarily a good indicator of performance in a different environment, such as the workplace. To an extent context is replacing content as the key factor in organisational learning. These realisations are leading to greater focus on workplace learning – learning in the context of work. Learning and work are merging.

The Importance of Experience

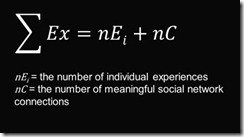

Bubbling along under the ‘social’ explosion has been an increasing awareness that experiences are critical to learning and performance.

The majority of learning is obtained through the experiences to which we are exposed. Many of our experiences are social, some are not.

Whichever way we gain our experience, we now know that they are vital building-blocks for our development. Learning how to ‘do’ something is far more important than learning ‘about’ something in terms of improving performance. We didn’t learn to ride a bicycle by learning Newton’s first law of motion, nor did we learn how to best utilise our professional skills through reading or being told about them. We learned through doing them or, at least, attempting to do them. The theory and explanations are often useful, but the real learning occurs through experience and practice.

The 70:20:10 Framework

Surprisingly, I need to place the following caveat almost every time I speak about the 70:20:10 model:

| ‘Proof’

70:20:10 is a reference model or framework. It’s not a recipe. It’s based on empirical research and surveys and also on a wide sample of experiences that suggest adult learning principally occurs in the context of work and in collaboration with others (as the great educational psychologist Jerome Bruner once said ‘our world is others’). 70:20:10 is being used by many organisations to re-focus their efforts and resources to where most real learning actually happens – through experiences, practice, conversations and reflection in the context of the workplace, not in classrooms. They have found the 70:20:10 framework a useful strategic tool to help them transform the way their organisations allocate resources and approach employee development – whether it’s leadership, management or individual contributor development. Anyone trying to 'prove' that the percentages fall in exact ratios, or anyone searching for peer-reviewed papers demonstrating the same is not only wasting their time, but clearly doesn't 'get it'. |

Some Background on 70:20:10

The fact that most development occurs outside formal learning has been known for many years, but the idea of specific ratios of the formal to informal split has only been in focus for the past 40 years or so.

In 1971 Allen Tough, emeritus professor at the University of Toronto, identified the fact that ‘about 70% of all learning projects are planned by the learner himself’ in his research published in ‘The Adult’s Learning Projects (the book is downloadable free). In a recent conversation, Prof Tough told me “both my books,‘The Adult’s Learning Projects’ and ‘Intentional Change’ look at the entire range of adult learning and change (not just work) but we found that 70:20:10 pattern.”

In 1996, 15 years after Allen Tough’s work, Morgan McCall and his colleagues Bob Eichinger and Michael Lombardo at the Center for Creative Leadership in North Carolina found from their observations that:

“Lessons learned by successful and effective managers are roughly:

70% from tough jobs

20% from people (mostly the boss)

10% from courses and reading”

Eichinger & Lombardo published some details in their book The CAREER ARCHITECT Development Planner (now in its 5th edition).

More recently (2010) a survey by Peter Casebow and Owen Ferguson at GoodPractice in Edinburgh, Scotland, found a similar split in their Survey of 206 leaders and managers.

Casebow and Ferguson found that informal chats with colleagues were the most frequent development activity used by managers (and one of the two activities seen as being most effective – the other one being on-the-job instruction from a manager or colleague). 82% of those surveyed said that they would consult a colleague at least once a month, and 83% rated this as as very or fairly effective as a means of helping them perform in their role when faced with an unfamiliar challenge. The other top most-frequently used manager development activities included search, trial-and-error and other professional resources.

Clearly, conversations (through informal chats with colleagues) and learning from the experience of others (through workplace instruction from their manager or a colleague - receiving the benefit of their experience and providing the opportunity for guided practice) are important in development of the surveyed group.

My colleague Jay Cross has listed other research into formal and informal learning (‘Where did the 80% come from?’) and explains why definitive figures have little meaning in the larger context. Jay identified a rough 80:20 split between informal and formal learning which he discussed at length in his Informal Learning book.

The 70:20:10 Framework in Practice

For me, at its heart 70:20:10 is all about re-thinking and re-aligning learning and development focus and effort. It involves stepping outside the classes/courses/curriculum mind-set and letting outputs drive the cart – thinking about performance improvement and helping people do their jobs better rather than spending the majority of time and effort on inputs – learning content, instructional design etc. Of course the inputs are important at times, but we need to keep our perspective. Content and design are not the most important inputs to the learning and capability development process.

It doesn’t matter if the job is simple or complex, whether it’s repetitive or highly varied, or if it’s driven by defined processes or requires extensive innovative and creative thinking. The principles are the same – the most effective and generally fastest way to improve and gain mastery will be through workplace and social learning.

In practical terms what does this look like?

Well, it may mean using any of these ‘70’ approaches:

- Identifying opportunities to apply new learning and skills in real situations

- Allocating new work within an existing role

- Increasing range of responsibilities or span of control

- Identifying opportunities to reflect and learn from projects

- Allocating assignments focused on new initiatives

- Providing the chance to work as a member of a small team

- Providing increased decision making authority

- Providing stretch assignments

- enhancing leadership activities, e.g.; lead a team, committee membership, executive directorships

- Setting up co-ordinated swaps and secondments

- Arranging assignments to provide cross-divisional or cross-regional experience

- Providing opportunities to carry out day-to-day research

- Providing opportunities to develop a specific expertise niche

- Allocating assignments to provide new product experience

Or any of these ‘20’ approaches:

- Encourage the use of colleague feedback to try a new approach to an old problem

- Establish a culture of coaching from manager/colleagues/others

- Encourage seeking advice, asking opinions, sounding out ideas

- Engage in formal and informal mentoring

- Embed informal feedback and work debriefs

- Encourage learning through team work

- Target building strong internal and external networks

- Build a culture of learning through teams/networks

- Support professional and industry association membership and external networking

- Encourage facilitated group discussion as a standard practice

- Use Action Learning

The above are just a few options available for development in the ‘70’ and ‘20’ zones.

Whose Responsibility?

When Learning professionals look at these lists they often remark that many of these activities are not in their bailiwick.

Of course this is correct. The responsibility for creating an environment where real learning occurs and opening up workplace learning opportunities is primarily in the hands of senior leadership and line managers. However, HR and Learning professionals have an important role to play.

A 70:20:10 approach does mean Learning professionals need to put a new lens on their responsibilities.

L&D has an absolute responsibility as enablers – to ensure leaders and managers understand their people development responsibilities AND have the capability and tools to deliver. This means there’s a role for Learning professionals in both the analysis of performance problems and in the design of the solutions where the outcome is intended to be improved performance through better understanding (knowledge) and skills.

70:20:10 and the Changing Role of L&D

All of this raises the question ‘does adopting the 70:20:10 framework change the role of the Learning function?’.

There is only one answer to this question. Yes - it changes the role fundamentally. And the change not only impacts L&D professionals but HR professionals as well.

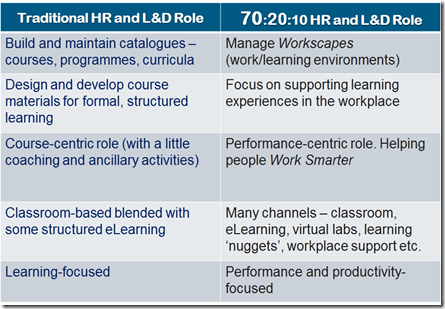

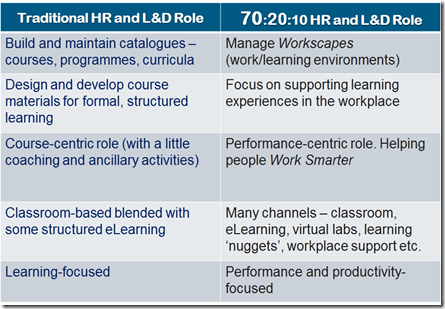

The table below indicates a few changes that need to occur when adopting 70:20:10 (or any model or framework focused on workplace and social learning):

These changes require new roles, new skills and new mind-sets. Learning professionals who have spent their time designing, developing and delivering formal, structured courses, programmes and curricula will need to adapt and develop their own capabilities.

My experience has been that many find the challenges of working within the new framework both challenging and rewarding. The 70:20:10 model certainly places Learning professionals much closer to their key stakeholders and to the white heat of their organisation’s Raison d'être. It has the potential to move L&D from a support function to the position of being a strategic business tool.

Tangible Actions to Deliver Results Through The 70:20:10 Framework

There are a number of actions that can be taken to deliver results through moving to greater focus on the ‘informal’ parts within 70:20:10. The table below splits them into three categories:

1. Actions to support the informal workplace learning process

2. Actions to help workers improve their learning skills

3. Actions that support the creation of a supportive organisational culture

Who is Using 70:20:10?

Over the past 18 months I have been engaged in work with researchers at DeakinPrime, the Corporate Education arm of Deakin University in Melbourne, Australia. Together, we have identified more than 60 organisations that have implemented the 70:20:10 model as part of their overall learning and development strategy. They include:

Nike, Sun Microsystems, Dell, Goldman Sachs, Mars, Maersk, Nokia, PriceWaterhouseCoopers, Ernst & Young, L’Oréal, Adecco, Banner Health, Bank of America, National Australia Bank, Boston Scientific, American Express, Wrigley, Diageo, BAE Systems, ANZ Bank, Irish Life, HP, Freehills, Caterpillar, Barwon Water, CGU, Coles, Sony Ericsson, Standard Chartered, British Telecom, Westfield, Wal-Mart, Parsons Brinkerhoff, Coca-Cola and many others.

| If you want an overview of the 70:20:10 framework with some examples, I have uploaded a SlideShare presentation HERE. |

------------------------------------------------------------

I would like to acknowledge my colleagues in the Internet Time Alliance and others who have contributed to some of the material in this post.

| There is a 60-page white paper titled "Effective Learning with 70-20-10: the new frontier for the extended enterprise" that I have written with Jérôme Wargnier of CrossKnowledge, a leading learning organisation headquartered in Paris. It was published in June 2011. The paper explores practical issues around the implementation of the 70-20-10 model. You can download it HERE |