The ‘learning’ referred to here is what we know as formal structured learning activities - classes, courses, programmes, and eLearning.

The argument goes like this.

Although formal learning only constitutes about 10-20% of the actual learning that occurs in organisations, it’s the visible part of the iceberg and the part where most of the budget and L&D resource is focused.

When we look at the structured learning taking place in organisations we find that the vast majority is content-rich and interaction-poor. The further up the hierarchy we go – from K12 to college through University and into training and learning in our working lives – we notice the majority of the structured learning we’re offered contains lots of content for us to ‘know’ but very little opportunity for us build capability to ‘do’. Yet action and ‘doing’ are at the heart of the value that people bring to themselves, to their work and to their organisations. Knowledge may provide scaffolding, but we’ve learned over the past 30 years or so that most of the knowledge we need to ‘do’ doesn’t have to be stored in our heads. There’s research that proves this point, but we only have to think about a common scenario to realise it ourselves.

Consider this. Your organisation has just rolled out a new online Finance system that requires you to use a new set of processes and forms when you complete your monthly expense claims. The new expense process that you need to follow has a number of steps, some of which are counter-intuitive (I’m sure we’ve all been faced with systems like this). Prior to system roll-out you’re required to attend a 2-hour instructor-led briefing/course along with all your colleagues. The instructor leads you through all six new processes that you’ll need to follow and describes the steps you’ll need to take in each. The expenses process had 12 steps. Some of the other five processes in the new system (raising and signing-off purchase orders, receiving goods etc.) have more steps, some have less. The course is content-rich. You are shown screen-shots of the new system and the instructor steps through each process (without giving participants the opportunity to practice on the system itself as go-live day is still in the future and the system isn’t yet stable). At the end of the course the instructor hands out a bound folder with all the screen-shots and descriptions of the processes.

When the time comes for you to complete your first expense claim (6-7 weeks after the training) do you:

a. Recall the processes you had been taught and easily step through them?

b. Find the folder and step through the processes from the screen-shots and descriptions?

c. Ask a colleague if they have used the system, if they have, get their help?

d. Call the helpline?

The chance is that you do either c. or d.

Why?

There are a couple of reasons. Firstly, very few people would be able to recall task detail weeks after being instructed. Even if you were tested and proved that you had ‘learned’ the processes at the end of the training. Post-training tests demonstrate short-term memory recall, not behaviour-changing learning. Hermann Ebbinghaus illustrated this and the exponential nature of forgetting in his famous 1885 experiment. In short, we forget around 40% of non-contextual information within the first 20 minutes of learning it if we don’t practice and reinforce the learning almost immediately. If you didn’t have the opportunity to practice the new Finance system processes, they were mostly gone from memory the next day. If you did, then didn’t have the opportunity to use the system again for a number of weeks, you’ve lost it from short-term memory again.

The second reason people ask others or call the helpline is because the vast majority of people simply don’t turn to detailed manuals when facing a problem and can’t remember the solution. They are more likely to turn to other people for help. Even if you pulled the folder off the shelf it’s likely that the amount of detail and the number of processes would have made it difficult to follow, and you will have lost the context with which they were described in the course anyway.

Part of the problem is that with learning we tend to concentrate too much on content and ‘knowing’ and too little on action and ‘doing’.

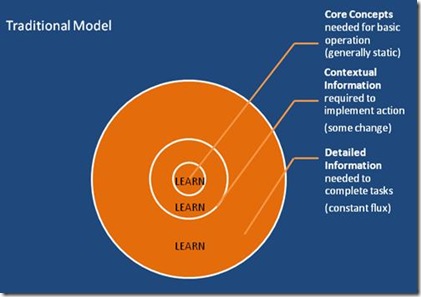

Traditional Model – Content-centric learning

The standard approach has been to expect people to learn all the content in a structured learning event – whether it’s an ILT or eLearning module, course or programme. Then ratify this learning through some type of assessment. The assumption is that if you pass the assessment, you’ve ‘learned the topic’. This is a naïve view of the learning process. Learning is about behaviour change, not short-term knowledge acquisition.

Most people who sit down to design learning experiences (even trained ‘instructional designers’) think first about the content. ‘How much content can I transmit to the recipients in the time I’ve allowed?’ or ‘Which content do I need to produce to meet the learning objectives?’ The knee-jerk reaction is to start with the content because somehow we seem to think that learning revolves around content. Content is information which we believe somehow transmogrifies into knowledge that will be useful to ‘do’ at some time in the future.

What’s Worth Knowing?

If we break what we need to know about using a process or procedure, for example, into its component parts we can start to get an understanding of what we need to learn and commit to long-term memory and what we don’t.

Firstly, there are some things that we simply have to commit to memory. These are the core concepts. In the diagram above the examples of core concepts are things such as ‘what does my job involve?’ and ‘what relationship does my role have with other departments?’ This is what I’d call the DNA of the role. Other core concepts that need to be committed to memory may involve some basic formulae, tools, marketplace practices and ‘the way we do things around here’. This is the content that any good new hire or induction training programme should include. These core concepts only change rarely. Structured learning/training works well to help with this memorisation.

Then there are things that we need to be familiar with, but don’t need to commit to memory in any detail. These are contextual elements that may vary depending on the context in which we need to use them. The Finance system processes are good examples of this. They are probably too complex to be learned correctly, and they are likely to change over time or depending on the role of the person using them. There’s no point committing the detail to memory, but it’s helpful to be familiar with the general structure and steps.

Finally there is the detailed task-specific content. The 12 steps in the process map and the field-level forms in the case of the Finance process. This is ‘stuff’ that you simply shouldn’t waste time learning, or trying to learn in a formal way. In many situations, task-specific content changes constantly. What was correct and up-to-date last week may not be correct and up-to-date today. It is simply a waste of time to include this content in structured learning/training courses and programmes. You may learn it by repeatedly doing it, and then you have the problem of ‘unlearning’ it when the process changes.

So, what’s the answer?

Find/Access Model – Content-right learning & Content-light learning

The answer is that in today’s rapidly changing world we need to learn just enough to be prepared to meet that rapid change. This means, in the words of John Seely Brown, we need to rethink what we need to learn, and how we learn. If most of what we learn is going to be rapidly made obsolete by change, then we need to change our learning models.

This brings us back to the initial premise – if we want to know more, then maybe we should learn less.

The Find/Access model addresses this challenge. This model takes a lot of the content out of 'learning' and moves it into the ‘familiarise’ and ‘find’ categories.

The Find/Access model focuses learning only on core concepts. Basic conceptual tools such as critical thinking skills, analytics skills, logic, search skills, data validation skills, research methodologies skills and so on fall into the core concepts bucket. This is the ‘stuff’ we need to learn.

Armed with the skills developed in the core concepts bucket, dynamic and detailed content can be obtained when it’s needed from ‘the cloud’ or from other sources – m colleagues, helpdesks, experts and so on.

There’s no need to incorporate the vast majority of the dynamic content we need in structured learning courses and events. In fact, doing so simply distracts and consumes time – which may be a benefit to the providers of learning courses and events, but is of little use in the process of improving performance.

However, we should be careful not to throw the baby out with the bathwater. To take this step we first need to ensure we have both the core find skills – the ‘MindFind’ skills (as my co-authors David James Clarke IV, Cameron Crowe and I describe in our forthcoming book MindFind) – and the tools to connect us to the information sources we need at the time we need them. Fortunately, Web application developments over the past 3-4 years are making this second task much easier for us.

Third Order Find Skills

As professionals involved in learning and performance improvement, we need to focus on helping others develop capabilities and skills in the core concepts bucket – the critical thinking skills, the analytical skills, logic, the search skills, and to develop some understanding of research methodologies.

(I’m sure there are other skills and capabilities that should be in this bucket and welcome any comments and suggestions you might have)

Fortunately, the development of third order approaches to the organisation, categorisation and labelling of information allows us to find what we need much more easily now than in the past. This is critical, and the designers of every structured course should reinforce the development of third order find skills and the use of third order find approaches. David Weinberger explains these third order approaches very clearly in his excellent book ‘Everything is Miscellaneous: the power of the new digital disorder’. Weinberger describes how tagging and metadata (third order classification) allow us to find information from our own contextual standpoint, rather than having to fit into some classifier’s context. Those of us who spent weeks and months shuffling academic library index cards in the past will understand how liberating the use of metadata has been.

As we develop these third order find skills the misplaced need for vast amounts of content in structured learning will fall away. We’ll need less structured learning overall. We’ll place more focus on learning by doing (through experience and practice), through interacting with others (network-building and conversations) and through reflecting on our actions. As a result, although we’ll be learning more overall, our structured learning will decrease. We’ll know more and the knowledge we need will be more relevant for action.

fro

fro