“The only person who behaves sensibly is my tailor. He takes new measurements every time he sees me. All the rest go on with their old measurements.”

—George Bernard Shaw

I’ve always enjoyed George Bernard Shaw’s writing. He was a man who made a great deal of sense to me. I started reading his books in my early teenage years and many of the ideas in them have stuck.

Shaw was a true Renaissance man - an Irish playwright and author, a Nobel Prize and Academy Award winner (how many can claim that double?) and a co-founder of the London School of Economics.

Shaw had a particular interest in education; from the way the state educates its children, where he argued that the education of the child must not be in “the child prisons which we call schools, and which William Morris called boy farms”; to the way in which education could move from teachers “preventing pupils from thinking otherwise than as the Government dictates” to a world where teachers should “induce them to think a little for themselves”.

Shaw was also a lifelong learner. Despite, or possibly because of, his own irregular early education he focused on learning as an important activity in life. He developed his thinking and ability through a discipline of reading and reflecting, through debating and exchanging ideas with others, and through lecturing. Apart from leaving a wonderful legacy of plays, political and social treatises, and other commentaries, Shaw also won the 1925 Nobel Prize for literature for “his work which is marked by both idealism and humanity, its stimulating satire often being infused with a singular poetic beauty". And, in 1938, the Academy Award for his screenplay for Pygmalion (later to be turned into the musical and film My Fair Lady after Shaw’s death. He hated musicals – some would say sensibly - and forbade any of his plays becoming musicals in his lifetime)

At 91 Shaw joined the British Interplanetary Society whose chairman at the time was Arthur C Clark (some interesting conversations there, I’m sure).

Shaw summed up his views on lifelong learning thus:

"What we call education and culture is for the most part nothing but the substitution of reading for experience, of literature for life, of the obsolete fictitious for the contemporary real."

Shaw’s Tailor

In the statement about his tailor Shaw was simply making the point that change is a continuous process and part of life, and that we constantly need to recalibrate if we’re to gain an understanding of what’s really happening. If we do this we are more likely to have a better grasp of things and make the adjustments and appropriate responses needed. It’s the sensible approach.

Shaw and Work-Based Learning

I recently came across Shaw’s quote about sensibility and his tailor again in Joseph Raelin’s book ‘Work-Based Learning: Bridging Knowledge and Action in the Workplace’. Raelin’s work is something every L&D professional should read.

The quote started me thinking about the ways we measure learning and development in our organisations.

Effective Metrics for Learning and Development

I wonder what Shaw would think if he saw the way learning and development is predominantly measured in organisations today.

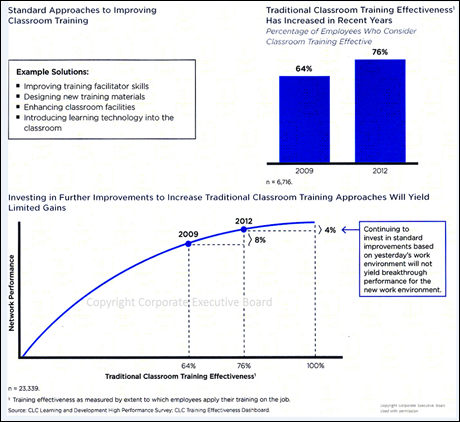

The most widely used measures for ‘learning’ are based on activity, not on outcomes. We measure how many people have attended a class or completed an eLearning module, or read a document or engaged in a job swap or in a coaching relationship.

Sometimes we measure achievement rates in completing a test or certification examination and call these ‘learning measures’.

The activity measures determine input, not output. The ‘learning’ measures usually determine short-term memory retention, not learning.

I am sure that Shaw would have determined we need to do better.

Outcomes not Activity

Even with today’s interest in the xAPI/TinCan protocol the predominant focus is still on measuring activity. It may be helpful to know that (noun, verb, object) ‘Charles did this’ as xAPI specifies. However extrapolating the context and outcomes to make any sense of this type of data requires a series of further steps that are orders of magnitude along the path to providing meaningful insight.

In many cases the activity measures simply serve to muddy the water rather than to reveal insights.

Attending a course or completing an eLearning module tells us little apart from the fact that some activity occurred. The same applies to taking part in a difficult workplace task or participating in a team activity.

Activity measurement does have some limited use. For instance when a regulatory body has defined an activity as a legal or mandatory necessity and requires organisations to report on those activities. these reports may help to keep a CEO out of the courts or jail. But this type of measurement is starting from the ‘wrong end’. A ‘learning activity is not necessarily an indicator of learning’ tag should be attached to every piece of this data.

There’s plenty of evidence beyond the anecdotal to support the fact that formal learning activity is not a good indicator of behaviour change (‘real learning’). For example a study of 829 companies over 31 years showed diversity training had "no positive effects in the average workplace." The study reported that mandatory training sometimes has a positive effect, but overall has a negative effect.

“There are two caveats about training. First, it does show small positive effects in the largest of workplaces, although diversity councils, diversity managers, and mentoring programs are significantly more effective. Second, optional (not mandatory) training programs and those that focus on cultural awareness (not the threat of the law) can have positive effects. In firms where training is mandatory or emphasizes the threat of lawsuits, training actually has negative effects on management diversity”

Dobbin, Kalev, and Kelly

Diversity Management in Corporate America

2007, Vol. 6, Number 4

American Sociological Association.

For further evidence as to the fact that training activity does not necessarily lead to learning (changed behaviour) we need look no further than the financial services industry. Did global financial services companies carry out regulatory and compliance training prior to 2008? Of course they did – bucketsful of it. Did this training activity lead to compliant behaviour. Apparently not. It could be argued that without the training things could have been worse. However, there’s no easy way to know that. The results of banking behaviour and lack of compliance were bad enough to suggest the training had little impact. I suppose we could analyse, for example, the amount of time and budget spent per employee on regulatory and compliance training by individual global banks and assess this against the fines levied against them. I doubt that there would be an inverse correlation.

(What is our response to the global financial crisis and the apparent failure of regulatory and compliance training? More regulatory and compliance training, of course!)

The Activity Measurement ‘Industry’

The ATD’s ‘State of the Industry’ report, which is published around this time of the year on an annual basis, is a case-in-point of the industry that has grown up around measuring ‘learning’ activity.

ATD has been producing this annual report for years (originally as the ASTD). The data presented in the ATD annual ‘State of the Industry’ report is essentially based around activity and input measurement – the annual spend on employee development, learning hours used per employee, expenditure on training as a percentage of payroll or profit or revenue, number of employees per L&D staff member and so on.

Some of these data points may be useful to help improve the efficient running of L&D departments and therefore of value to HR and L&D leaders, but many of the metrics and data are simply ‘noise’. They certainly should not be presented to senior executives as evidence of effectiveness of the L&D function.

To take an example from the ATD data, the annual report itemises ‘hours per year on ‘learning’ (which means ‘hours per year on training). The implicit assumption is that the more that are hours provided, the better and more focused the organisation is on developing its workforce.

But is it better for employees in an organisation be spending 49 hours per year on ‘learning’ than, say, 30 hours per year? These are figures from the 2014 ATD report.

Even if one puts aside the fact that as a species we are learning much of the time as part of our work and not just when we engage in organisationally designed activities that have a specific ‘learning’ tag, this is an important point worth considering.

It could be argued that organisations with the higher figure – 49 hours per year – are more focused on developing their people. It could equally be argued that these organisations are less efficient at developing their people and simply take longer to achieve the same results. It could be further argued that the organisations spending more time training their people in trackable ‘learning’ events are simply worse at recruitment, hiring people who need more training than the ‘smart’ organisations that hire people with the skills and capabilities needed who don’t need much further training. We could dig further and ask whether spending 49 hours rather than 30 hours is indicative of poor selection of training ‘channel’ – that organisations with the higher number are simply using less efficient channels (classroom, workshop etc.) than others who may have integrated training activities more closely with the workflow (eLearning, ‘brown bag lunches’, on-the-job coaching etc.). Even further, is the organisation with the 49 hours per year simply stuck in the industrial age and using formal training as the only approach to attack the issue of building high performance – when it could (and should) be using an entire kitbag of informal, social, workplace and other approaches as well?

One could go on applying equally valid hypotheses to this data.The point is that activity data provides few if any insights into the effectiveness of learning and provides only limited insight into the efficiency of learning activities.

So why is there an obsession to gather this data?

Maybe we gather it because it is relatively easy to do so.

Maybe we gather it because the ‘traditional’ measurement models – based on time-and-motion efficiency measures – are deeply embedded. These time-honoured metrics developed for an industrial age are not the answer. We need to use new approaches based on outcomes, not inputs.

Learning is a ‘Messy’ Process

Sometimes we attend a structured course and learn something new and then apply it our jobs. At other times we attend a structured course and meet another attendee who we then add to our LinkedIn connections. At some later point we contact this LinkedIn connection to help solve a problem – because we remember they told an interesting story about overcoming a similar situation in their organisation or part of our organisation.

This second case falls into the ‘messy’ basket. It is almost impossible to track and ‘formalise’ this type of learning through data models such as xAPI – unless we’re living with the unrealistic expectation that people will document everything they do at every moment in time or that we track every interaction and are able to draw meaningful inferences. Even national security agencies struggle doing that.

More frequently than learning in structured events we learn through facing challenges as part of our daily workflow, solving the problems in some way, and storing the knowledge about the successful solution for future use. We also increasingly learn and improve through our interaction with others – our peers, our team, our wider networks or people we may not even know.

So how do we effectively measure this learning and development? Is it even worthwhile measuring?

I believe the answer to the second question is ‘Yes, when we can gain actionable insight’. It is worthwhile measuring individual, team and organisational learning and development to understand how we are adapting to change, innovating, improving our customer service, reducing our errors and so on.

This type of measurement needs to be part of designed performance improvement initiatives.

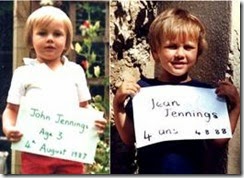

Furthermore, measuring learning frequently via performance improvement is better than measuring it infrequently.

One of the challenges the annual performance review process has come under recently is that the insights (and data) collected as part of the process is too infrequent. Companies like Adobe have already abolished annual performance reviews and replaced them with regular manager-report informal check-ins to review performance progress and any corrections needed. Fishbowl, a Utah-based technology company, has gone a step further and not only abolished annual performance reviews but also abolished its managers. Companies such as W.L.Gore have been treading this path for some time. It is clear that the annual performance review, a metrics approach based on ling (long) cycle times and relatively stability, will give way new, more nuanced approaches. A parallel path to learning metrics.

Outcome Measurement

One of the challenges for L&D is that the useful outcome metrics are not ‘owned’ by them. These are stakeholder metrics not ‘learning metrics’.

If we want to determine the effectiveness of a leadership development programme the metrics we should be using will be linked to leadership performance – customer satisfaction, employee engagement levels, organisational profitability for instance.

If we want to measure the impact and effectiveness of a functional training course the metrics we should be using are whether productivity increases, first-time error rate decreases, customer satisfaction rises, quality improves and so on.

If we want to measure the benefits from establishing a community for a specific function or around a specific topic the metrics we should be using will be linked to similar outputs – productivity increases, increase in customer satisfaction etc. Also we should be measuring improvements in collegiate problem-solving, cross-department collaboration and co-operation and similar outputs in the ‘working smarter together’ dimension.

These metrics need to be agreed between the key stakeholders and the L&D leaders before any structured learning and development activities are started. Without knowing and aligning with stakeholder expectations any structured development is just a ‘'shot in the dark’.

L&D also needs to consult with its stakeholder on how to obtain these metrics.

Some data may be readily available. Customer-facing departments, for example, will regularly collect CSAT (Customer Satisfaction) data. There are a number of standard methodologies to do this. Sales teams will inevitably have various measures in place to collect and analyse sales data. Technical and Finance teams will have a wealth of performance data they use. Other data will be available from HR processes – annual performance reviews, 360 feedback surveys etc.

These are the metrics that will provide useful insights into the effectiveness and impact of development activities managed by the L&D department.

Obviously these data are more nuanced than the number of people who have completed an eLearning course or have attended a classroom training course, but they are more useful. Sometimes the causal links between the learning intervention and the change in output are not clearly identifiable. This is where careful scientific data analysis together with the level of trust relationship between L&D and stakeholder are important. The 10-year old study by the (then) ASTD and IBM ‘The Strategic Value of Learning’ found that:

“When looking at measuring learning's value contribution to the organization, both groups (C-level and CLOs) placed greater emphasis on perceptions as measures”

One C-Suite interviewee in this study said “We measure (the effectiveness of learning) based on the success of the business projects. Not qualitative metrics, but the perceptions of the business people that the learning function worked with.”

New Measurements Every Time

Returning to George Bernard Shaw, one of the challenges of effective measurement is the need to review the metrics needed for each specific instance. No two situations are identical, so no two approaches to measuring impact are likely to be identical. Or, at least, we need to check whether our metrics are appropriate for each measurement we undertake.

As Robert Brinkerhoff says, “There is no uniform set of metrics suitable for everyone”.

Brinkerhoff’s Success Case Method addresses systems impact rather than trying to isolate the impact of learning individually as the more simplistic Kirkpatrick approach attempts. Brinkerhoff’s approach moves us from input metrics to stakeholder metrics – certainly on the right road.

What is also required in defining and agreeing metrics that will be useful for each and every project is a process of engagement with stakeholders and performance consulting by learning professionals.

These approaches require a new way of thinking about measurement and new skill for many L&D professionals but, like Shaw’s tailor, we need to ‘behave sensibly’ and stop wasting our time on trying to ‘tweak’ the old methods of measurement.

Learning, and measurement, are both becoming indistinguishable from working.

-------------

Photographs:

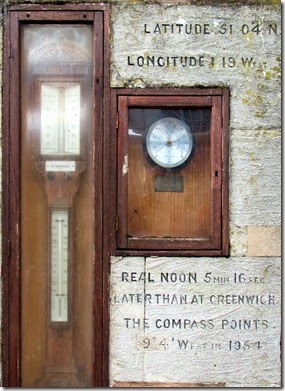

Shaw: Nobel Foundation 1925. Public Domain

Tape Measure: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0

#itashare