702010 towards 100% performance

by Jos Arets, Charles Jennings & Vivian Heijnen

Copyright: Sutler Media

Language: English

Pages: 313

Size: 30.5cm x 23.5 cm (12 X 9.25 inches)

It provides the first comprehensive and practical guidance for supporting the 70:20:10 model.

BUY THE BOOK: www.702010institute.com

The book is divided into 100 numbered sections across 313 pages in ‘coffee table’ format. Just eight of these sections are devoted to the problems. The other 92 provide solutions.

-

Full explanations of how the 70:20:10 approach can be used to help overcome the ‘training bubble’

-

Descriptions of five new performance-focused roles to support the use of 70:2010

-

The detailed tasks that need to be executed in each of these roles. Task lists, models, guidelines.

-

Checklists to rate your own organisation’s ability to deliver the critical tasks supporting 70:20:10

-

Nine ‘cameos’ written by leading thinkers and practitioners including Dennis Mankin (Platinum Performance), Nigel Harrison (Performance Consulting), Clark Quinn (Quinnovation), Jane Hart (Centre for Learning & Performance Technologies), Bob Mosher (APPLY Synergies), Jack Tabak (Chief Learning Officer, Royal Dutch Shell), Jane Bozarth (US Government) and others.

-

12 page bibliography with a wealth of references to supporting papers, books, articles, case studies and other material.

Start with the 70. Plan for the 100.

Extending Learning into the Workflow

Many Learning & Development leaders are using the 70:20:10 model to help them re-position their focus for building and supporting performance across their organisations. They are finding it helps them extend the focus on learning out into the workflow.

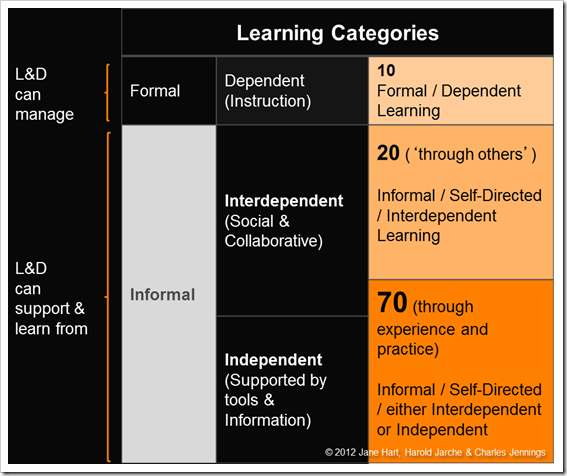

The 70, 20 and 10 categories refer to different ways people learn and acquire the habits of high performance. ‘70’ activities are centred on experiential learning and learning through support in the workplace; ‘20’ solutions are centred on social learning and learning through others; and ‘10’ solutions are centred on structured or formal learning.

- 10 solutions include training and development courses and programmes, eLearning modules and reading.

- 20 solutions include sharing and collaboration, co-operation, feedback, coaching and mentoring.

- 70 solutions include near real-time support, information sources, challenges and situational learning.

Traditionally, L&D has been responsible for services in the ‘10’, and sometimes for more structured elements in the ‘20’ (such as coaching and mentoring programmes).

The ‘10’ has primarily involved designing, developing and implementing structured training and development interventions. When done well, these ‘10’ interventions can successfully help to build performance. However, learning which occurs closer to the time and place where it is to be used has a greater chance of being turned into action and result in performance improvement.

The closer learning is to work, usually the better.

In other words, 10 solutions are likely to have less business impact and provide less value than the 70 and 20 solutions in the long run.

Increasing the Value of Learning

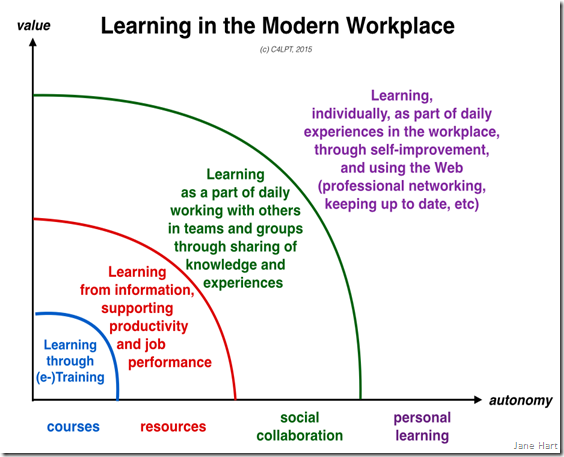

That’s an important point worth repeating. As learning is highly contextual, and improved performance is the critical desired outcome, the closer learning occurs to the point of use then the greater is it’s likely impact.

This point is illustrated in the diagram below. This is taken from the 702010 Towards 100 Percent Performance book. As you move from the 10 and closer to the workflow (where most of the 20 and 70 happen) the potential for impact and realised value increases.

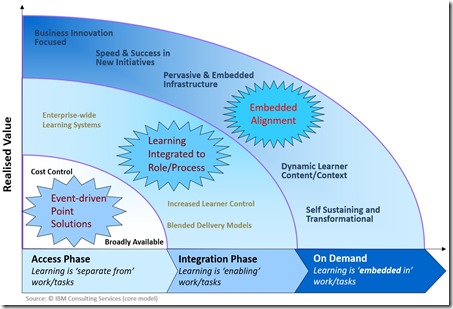

This aligns with the model developed by IBM Consulting Services some years ago (see below) developed to explain the evolution of learning and increased value of on-demand services aligned with current and future business needs.

The IBM model suggests three phases – access, integration, and on-demand. As learning moves from being separate from work, through enabling work, to being embedded in work the realised value potential increases.

De Grip (2015)[1], along with a number of other academic researchers, have also observed that informal learning – mostly 20 and 70 activities - is much more important than formal training when it comes to developing people in organisations.

Start With the 70

As learning is likely to be most effective when it occurs nearest the time and place of use, then it is best to always start with the 70 when developing solutions to address performance problems.

This may seem counter-intuitive to many L&D professionals.

In the past we’ve usually started with the ‘10’. We identified a performance challenge (often presented as a ‘training problem’) and then decided whether the solution should be face-to-face or digital. In other words, do we develop class/workshop or eLearning.

This simple binary option approach will not deliver optimum value. Selection of the ‘channel’ is made only from ‘10’ options. ‘70’ and ‘20’ options tend to be ignored.

The 70:20:10 approach recommends that solution design should start with options that are most likely to produce fast and efficient results, and those that are most likely to realise the greatest value. These are the solutions that are integrated into the workflow – the 70 and 20 solutions.

This recommendation is supported by a number of findings including those recently reported in a paper titled ‘The Secret Learning Life of UK Managers’.

‘The Secret Learning Life of UK Managers’

GoodPractice and Comres

November 2015

This report found that, for managers at least, the two key factors that most influence how people in work choose to learn are:

[a] ease of access, and;

[b] speed of result.

The research for this report was based on 500 interviews with managers carried out by Comres[2], a specialist polling and data gathering/analysis organisation.

The principal finding of this study was:

“How effective a learning option is perceived to be is much less important than how accessible it is and how quickly it produces a result. This applies across all approaches, whether online or offline.”

Plan for the 100

The key for effective 70:20:10 design is to plan for the 100.

What this means is that any solution is likely to comprise a variety of parts; some 70, some 20, and some 10.

It is important to avoid solutioneering within the 10 at the outset. As such, it is important to design with both the result in mind and with the ‘100’ in mind. This immediately extends both thinking and practice beyond the 10.

In other words, it is critical to maintain a clear focus on the desired performance outputs and, at the same time, use the principle of designing a total solution – incorporating 70, 20, and 10 elements as needed (and in this order).

Starting with the 70 and designing for the 100 is a good mantra to adopt if we are looking to deliver effective learning solutions.

Visit the 70:20:10 Institute site at www.702010institute.com

[1] De Grip, A. (2015). The importance of informal learning at work. On: http://wol.iza.org/articles/importance-of-informal-learning-at-work-1.pdf.

[2] http://www.comres.co.uk/