![Milk carrier Frederick (Fred) Jones delivers full milk cans at Drouin's co-operative milk factory, Drouin, Victoria [picture] / Milk carrier Frederick (Fred) Jones delivers full milk cans at Drouin's co-operative milk factory, Drouin, Victoria [picture] /](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhulZ11roMWscrNtsYMVlI4lxRkm4RQjxzSsYOwlvUL-GFR3irvpUP5R6-Bv-Y5sa9GX5I_I3932kRwRE-UAQOScFyThQ2qLpy5ppXnDJG8hgnBVVW2w_EHtCyI0bVSAjzKLPslYlurtWqP/?imgmax=800) During a meeting at Cambridge University around 30 years ago I was thoroughly chastised by a Cambridge academic.

During a meeting at Cambridge University around 30 years ago I was thoroughly chastised by a Cambridge academic.

I’d used the phrase ‘learning delivery’ when describing computer-supported collaborative learning (CSCL) approaches. CSCL was one of the hot pedagogical approaches of the day – when network-based learning was in its relative infancy.

“Charles, my dear fellow”, said the Cambridge man, “we may deliver milk, but learning is something that is acquired, never delivered”.

Of course he was right. I’d been sloppy with language. What I’d meant by ‘learning delivery’ was ‘providing the resources and environments that help learning and, by inference, improved performance, to occur’. Learning takes place in our heads. We alone make it happen.

I guess the phrase I’d used was a shorthand. However, it was the last time I ever used it. It conveyed an inaccurate message.

Sometimes language does matter.

The myth of knowledge transfer

The same could be said of the phrase ‘knowledge transfer’. We can’t and don’t transfer knowledge between people. We transfer information. A subtle but important distinction.

The same could be said of the phrase ‘knowledge transfer’. We can’t and don’t transfer knowledge between people. We transfer information. A subtle but important distinction.

We can create and use techniques and approaches that help and facilitate knowledge acquisition. We can share information in the form of data and our own insights. We can create environments where people are likely to have their own insights – their lightbulb moments – and we can help people extract meaning and learn through their own experiences.

But we don’t transfer knowledge. Not between people, or even between organisations.

Of course exposure to other people is one of the primary ways we learn and improve our performance. Some organisations, such as Citibank, refer to their 70:20:10 approach as the 3Es – learning through experience, exposure and education. The ‘exposure’ part is important.

Exposure to other organisations’ experiences can also be very useful for our own organisation’s learning and development, but no two organisations are exactly the same. If we package up the acquired data, information and practices in one organisation it’s extremely unlikely that they can be simply unpacked and used as-is with the same effect in another, no matter how closely aligned the organisations might be. The ‘knowledge transfer’ model doesn’t even work between organisations in industries with relatively standardised process . What works for Mercedes is unlikely to work for Ford without quite a bit of thought and customisation.

The incessant desire to hear about ‘best practice’ is really a need to hear about good practice and emerging practice (Dave Snowden explains the important differences extremely well in his Cynefin Framework). In other words, people are actually asking ‘tell me about the things that work for you. They might give us some good insights if we can apply them in our own way’. There is no ‘best practice’ where there are different environments and processes.

It’s the case of language carrying deeper meaning again, and often distorting our thinking – in this case building a belief that there is a ‘best way’ that can be picked up and transferred. But there is no ‘best practice’ in anything but very simple situations.

The problem with learning transfer

The knowledge transfer myth and best practice misunderstanding have striking similarities with the ‘learning transfer’ problem, in both senses of the phrase – transfer of learning into heads and transfer of learning from heads into action.

Of course we don’t ‘deliver’ or ‘transfer’ learning either. The way we learn best is when the stimuli are relevant to our need. Learning is a highly contextual activity. The closer to the point of use that it occurs the more effective it is likely to be. There’s a number of reasons for that.

When we develop a new capability, for example, it’s best to acquire it within the context we’re going to use it. Then apply it as quickly as possible. In that way we’re much more likely to remember how to use it correctly, and more likely to be able to recall it again later.

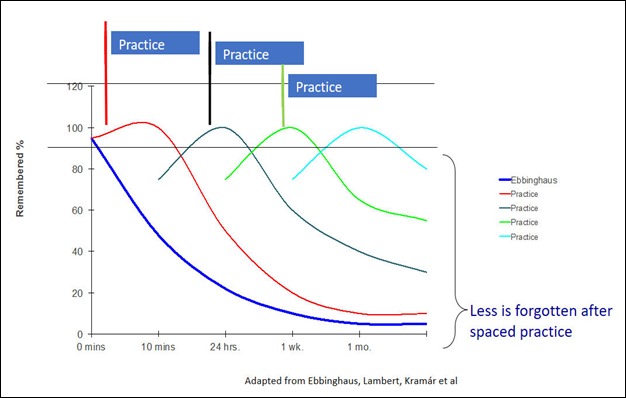

We know also that practice is critical for retention, and that spaced practice has been shown to provide an effective mechanism to help memory retention over the longer term, so we can recall when we need it. Spaced practice, procedural learning, distributed practice, priming and other methods have a long history of demonstrating greater persistence of learning resulting in improved performance.

Eliminating the Learning Transfer Problem

There can be no challenge to the fact that a major problem exists with learning transfer, and that it has existed for years. It could be argued that the problem came into existence the day we separated training from the workplace.

“Estimates of the exact extent of the transfer problem vary, from Georgenson’s (1982) estimate that 10% of training results in a behavioral change to Saks’ (2002) survey data, which suggest about 40% of trainees fail to transfer immediately after training, 70% falter in transfer 1 year after the program, and ultimately only 50% of training investments result in organizational or individual improvements” (from Burke & Hitchens)

One of the best ways to overcome the learning or training ‘transfer’ problem can be simply to eliminate the need for it.

“"Talent development specialist Boudewijn Overduin says the solution to this problem is simple: ‘If you don’t train, you don’t have a transfer problem’.” (from our 702010 towards 100% performance book)

If learning is embedded in the daily flow of work, rather than away from the workflow, the idea that we need to develop ways to ‘transfer’ that learning into practical use disappears. When there’s little or no gap between the two there is no ‘transfer problem’. When we learn from work (rather than learning to work), even better.

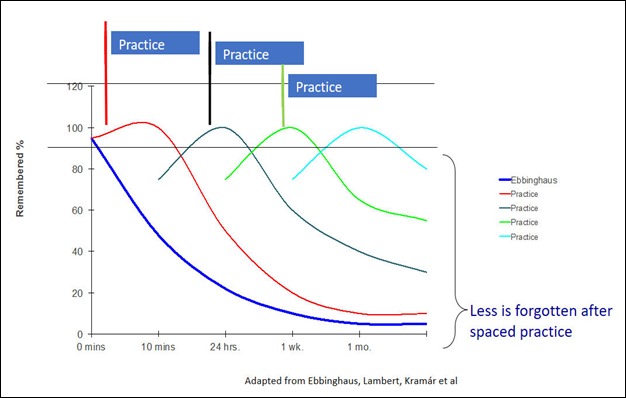

Of course this is easier said than done. Especially as most organisations have an often large and continuing investment in formal training and development, the vast majority of which is carried out away from the workflow. The overwhelming majority of staff development budget is spent on the acquisition, design, development and delivery of formal development in the form of programmes, courses, and eLearning modules.

If just a fraction of that resource was spent on embedding learning into the workflow – through designing solutions that start with the ‘70’ in 70:20:10 parlance (learning through working) and embrace the ‘20’ (learning though working together) before adopting the ‘10’ (formal training and development) – then the transfer issues become minimal or are fully eliminated.

This approach needs a detailed understanding of the issues to be addressed, the ability to architect and create solutions that stretches well beyond instructional design, and the trust of stakeholders so they play their part in the process.

There are some important reasons to adopt this approach, expressed well by Jay Cross in his contribution to our ‘702010 towards 100% performance book:

Our learning ecologies are entering a do-or-die phase similar to global warming. Management is demanding that the workforce be more effective but ‘what got us here

will not get us there’. We must nurture learning in the workplace or face corporate meltdown.

Beyond schooling

Work on hybrid learning environments (see Zitter and Hoeve, 2012) suggests that most of the work L&D departments carry out is still firmly grounded in school-based learning where ‘learning is central and organised in a formal curriculum or learning paths with predictable outcomes and a focus on explicit knowledge and generalised skills’.

On this side of the dimension, learning tasks are constructed to facilitate knowledge acquisition and knowledge is considered as a commodity that can be acquired, transferred and shared with others (Sfard, 1998)

When L&D moves beyond schooling, learning is characterised as ‘becoming a member of a professional community’ (Sfard) and is acquired in realistic, real work situations.

By melding working and learning, and becoming immersed in real problems and real experiences, we eliminate the knowledge and learning transfer problems. The future role of L&D, and of managers, is to make this happen. That’s an area where the 70:20:10 approach and the 70:20:10 methodology can really help.

-----------

References

Burke, L. and Hitchens, H. (2007) Training Transfer: An Integrative Literature Review

Zitter, I. and A. Hoeve (2012), Hybrid Learning Environments: Merging Learning and Work Processes to Facilitate Knowledge Integration and Transitions, OECD Education Working Papers, No. 81, OECD Publishing.

Sfard, A. (1998), “On Two Metaphors for Learning and the Dangers of Choosing just One”. Educational

Researcher, 27(2), 4–13.

Photographs:

Milk carrier Fredrick (Fred) Jones delivers full milk cans, Drouin, Victoria, Australia. National Library of Australia. Wikimedia Commons

Pancakes and Cream cake. Cake and photograph by Lindsay Picken, LP Cakes, Kirkcudbright, Scotland. Used with permission

For more information about the 70:20:10 model and the 70:20:10 methodology, visit the 70:20:10 Institute site.

Many may not have noticed it at the time, but the world of learning changed in 1990.

Many may not have noticed it at the time, but the world of learning changed in 1990.

![Milk carrier Frederick (Fred) Jones delivers full milk cans at Drouin's co-operative milk factory, Drouin, Victoria [picture] / Milk carrier Frederick (Fred) Jones delivers full milk cans at Drouin's co-operative milk factory, Drouin, Victoria [picture] /](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhulZ11roMWscrNtsYMVlI4lxRkm4RQjxzSsYOwlvUL-GFR3irvpUP5R6-Bv-Y5sa9GX5I_I3932kRwRE-UAQOScFyThQ2qLpy5ppXnDJG8hgnBVVW2w_EHtCyI0bVSAjzKLPslYlurtWqP/?imgmax=800)